|

My name is Dan Rogger and this is my blog (you can find out more about me at my About me page of my main web site). It aims to present my beliefs on how to live contemporary life in a philosophical way (or how I have tried to confront some of the challenges I face on an everyday basis). Every other week I aim to write a short piece on a topic of note from the weeks gone by.

The below are letters to my generation. They are, I hope, a collection of notes that explore the idea of a social philosophy - a philosophy anchored in the idea that society is the fundamental unit of philosophical analysis. Please send your thoughts and replies to drogger@worldbank.org.

Postings (in reverse chronological order)

On Creation

2nd December 2024

The poem was text yet not words;

It drew you to settings unheard;

But felt.

Formed on the cusp of the soul;

Diving deeply, to waters told and untold.

The poem, like a prayer;

A conversation with God.

The words chosen in flow;

Through a lightning rod.

The poem, it digs into the earth that is you;

Like a plough digs into Spring clod anew;

And gives light to that which is dark;

That which is alive under the bark.

It's author, The Poet, drew breath when it fell.

For though it was given to this author to tell,

It's depths were discovered and drawn out for display,

Gathered and moulded from pre-existing clay.

It's author, The Poet, sat with this thing,

This drafted note through which Art seemed to sing.

Like a spent tool, but sharpened by work;

Given dignity through creation, where doubt used to lurk.

It's author, The Poet, rested her hand;

Echoing adventure in a promised land.

Her pen spilt; Her mind returned;

Yet still here in the grey, she yearned.

Words.

More than any ingredient,

Change their flavour depending on how they are laid.

Though the possibility of ambrosia stalks;

They so rarely combine like this particular raid.

Words that seemed base;

Somehow in this poem had been placed;

To rest.

Here.

Where they could bridge to Love, and Hate;

And all that falls between.

Words that elevated and pulled;

Tearing a whole in your soul,

So as to let you pass;

To that which is true.

The woman who wrote sat back.

She read and felt.

And wrestled with Self.

That which questions why we create.

The woman who wrote thought this was a chance.

To be recognised as the tool she was.

To speak out and be heard.

Not to sit and read, but be read.

The women who wrote was like us.

Thinking of what could be for me.

For what is the future?

And what might it be?

She rose.

Time would tell of what the poem would mean.

Would mean for her self.

Would mean for the soul.

She rose to find nails, and a hammer or two;

And struck deep through the paper;

As she posted that which was true.

On doorposts close by.

She rose only to fall.

That sadness after striving;

And yet recognition does not come;

Was arriving.

So smitten with her creation;

She tried once again.

Her sweat carrying her soul,

Her hand now driving her pen.

So smitten with her creation,

At first the work was good.

But with smiles and appreciation,

Her audience simply stood.

No bells for her.

For the spark and the clod.

For what deserved recognition.

Was mostly between her and God.

So smitten with her creation,

She formed a pact with herself;

Nothing matters but striving,

I shall not leave this one on the shelf.

So smitten with her creation,

Onwards she pushed,

And now showered the world with love;

Not for her self, but for the good.

She rose to speak,

Not about her pen, nor the process of the thing;

But because her soul had found a place;

About which to truly sing.

She rose up again.

Once more. Once more.

She rose up again,

Once more.

She rose to sit with her poem;

With our poem.

Not to hear the crowd's praise,

Or their roar.

The woman who wrote was changed by her writing.

That is the point of the thing.

Of bridging beyond the self.

To the darkness we try to sing.

The woman who wrote was applauded.

For now she was more than herself.

She shone with the light of the poem.

Having grown to appreciate her wealth.

The woman who wrote was no longer.

What remained was more Poet than Self.

An echo not of your ego;

But of the whole, and the bridge, and the shelf.

Word arose of her actions.

It was known what she could do.

She lingered in the limelight.

But now the reasons to do so were few.

Words now a tool for disturbance,

For disturbing that which is and will be.

For toiling and not relenting.

Still waters to plough and to see.

Words. Used so freely.

Listening to us as we write.

And burning a hole that is of our doing.

Unless we are using words right.

It's author, The Poet, is passed now.

Her epitaph, her remains and her gifts.

The echo of her life, the hole she had forged,

Edges blurred; spilt into a thousand rifts.

It's author, The Poet,

Is transcendent.

No more writer;

But thresher and threshed.

It's author, The Poet, is now clay herself;

A source in the pre-existing soil.

For others to mould, mine and scour;

And be remade by their frightening toil.

The poem we forge is Creation.

That we mine from the depths of our soul.

That weighs amongst others in darkness.

Ready to burn in our fires like coal.

The poem dissolves our boundaries.

In the darkness no borders are seen.

So we scrape at the walls of existence;

Guided only by what might have been.

The poem forges us in its building;

In its fires we burn like coal.

In creating we are the created;

So long as we make that our goal.

Back to top

On Representing Social Philosophy

28th September 2024

The Net of Society

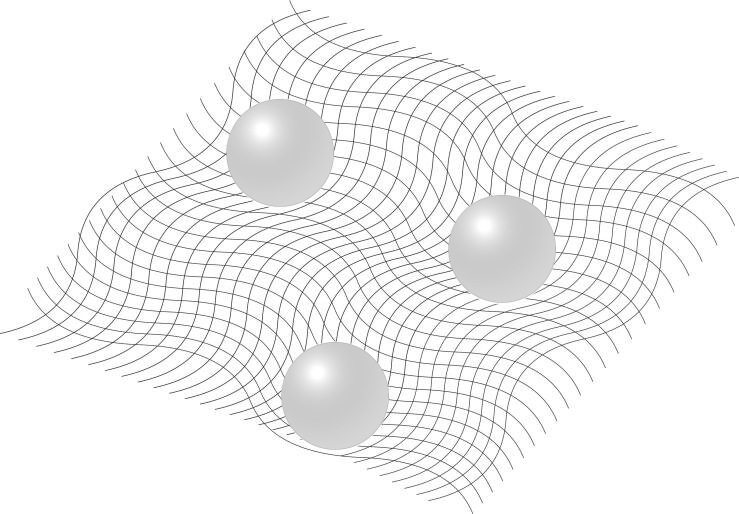

I was very taken with the way my wife imagined individualism versus social philosophy this week. Suppose we are balls sitting on a net. As the balls move around, they change the impression they make on the net and the environment in which the other balls exist.

I imagine those balls being bundles of the net, and the net being society. So as the balls move, they are both shifting the net underneath the other balls, but also tugging at what makes them up. If a ball pushes too deep into the net, it distorts the space around it to make it central, and forces the other balls to fall towards it. If a ball disengages with the net, it also changes the shape of the space around others. Thus how we engage with society changes the social and philosophical space around others.

One aspect of this imagery I particularly liked is that the shape of the net could be said to represent the nature of a society. With obvious links to the imagery used in physics, it touched the analytical part of my world. And it made me wonder what one might argue is a `good' shape of this societal net.

Returning to the US from Japan, I find this imagery helps me bridge the interactions I had in both places. In Japan, it felt as though there was a sincere appreciation of both the net's existence, and the challenges of truly understanding the net. Much of Shinto philosophy attempts to sketch out features of the net, but makes clear the limits of this exercise. The conceptions I was taught, and the rituals, practices and behaviours I observed and participated in, all seem to be reaching towards the net, and its relationship to the bundles within it.

In the US, it feels as though there is far less appreciation that any net connects us. Rather, the focus is on the balls. It feels that there is limited time spent on investigating what joins us. This is true in both a conceptual sense - I don't experience conversations about those linkages here. But certainly in a practical sense - there is no equivalent practices in the US to those I experienced in Japanese Shinto culture.

It could be that in the US, the space between persons is assumed to be empty space. That society is simply the product of multiple individuals, rather than there being an innate flow between them. There are versions of this from around the world. For example, Margaret Thatcher famously stated in 1987 that, "... they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first." It is just that my contemporary experience of living in the US reflects this position.

It is not that I am being critical. Rather I sincerely cannot appreciate what the society of the US believes is the connecting material between individuals in a philosophical sense. My best guess is that it is a grand view of rights. That the society of the US has almost `legislated' the nature of the net between individuals. However, such rights seem to be limited in their application amongst individuals here, and as such I find the experience of understanding the net in the US challenging. I would love to better understand how the net as my wife has describe it is observed here, in the way that Shinto language and practice made so much easier in Japan.

Individualism could be said to be viewing this setup such that you only see the balls. In that case, one is unlikely to appreciate multiple things about the world. One, that we are in fact bundles of society. Two, that our actions reshape the net on which others sit. And three, that as we move we tug at what makes up the bundles of others. Seeing the world only for the bundles of persons misses the innate connection between what makes us up. It is, in the view of social philosophy, an incomplete vision of the world.

Back to top

Art Experiment: Volunteer

11th August 2024

As I sit writing this, a moment of art is dying; its artistic presence is decaying back to normality.

I sit in the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, at ease with the death of my own creation. This is in contrast to the stability of the art that surrounds me here. For unlike traditions that would preserve art or let it decay instantly before it can be commoditised, art experiments must remain long enough to plausibly be noticed, but no more.

This morning, I came to the temple steps of the Ueno Toshugo shrine. As I had done before, I swept the steps of natural debris as a public service to those who use them. But today I swept only the right-hand side as you are ascending them, creating a contrast between the structured cleanliness on the one hand, and the naturally-cultivated debris on the other.

Volunteer

As I swept, one person stopped to ask whether I was a `borantia' (volunteer). Yes, I told them. But in truth, I was doing something in between volunteering and counselling. In the asymmetry of my actions with regards the debris on the steps, I was trying to better understand the tensions Japan has instilled in me. The structured curation of the physical, cultural and social space the country excels in contrasts with the brash struggle in which I am raising a family.

The Beauty of Structure

Swept clean, the homogeneity of the side without debris seemed to be closer to the abstractions to which I aspire. Yet the debris could be viewed from myriad angles, some instilling a more local sense of beauty, struggle and perhaps reality.

The Beauty of Disorder

As new leaves fell onto the right-hand side of the steps, the cleanliness was disturbed by nature’s yearning for presence. Preservation of the divide I had created was time bound, and with graceful decay, my division will fade.

Nature Decaying Art

Back to top

Ripples

11th July 2024 | Inspired by the Haya River as seen from the Yumoto Bridge in Hakone, Japan

As two ripples echoed out across a river, the broader one said to its kin: "We are ripples on the great river of society."

"Does it matter that we do not understand the course of the river as a whole?" its kin replied.

"The river does flow, and is interrupted, and is moved."

The ripples gently followed their course a little further, before the succeeding ripple began its questioning once again.

"What morality is there in a particular course? In a particular rock finding a particular place?"

"Rivers change. Rocks move. And we flow. The ripples that came before ours formed the course for us."

"Is our history our morality?"

"We are ripples that can harden, and fall to the bed of the river. We can leave a deposit towards a more influential sediment, that along with the deposits of other ripples becomes of greater influence to the course of the river."

"What right do we have to alter the course of the river when we do not understand its course?"

"If we can change our course and yet do not, that is a morality in itself. Why even a single rock can change the course of a river."

"Do we have a right to set a sediment on the base of the river?"

"Some ripples flow in a way that strengthens the river. Others weaken its banks. Sediment is more powerful than it seems. Ripples think least about that which is underwater, and yet it has most influence over the river's course."

"Should a sediment rise to become a rock?"

"It is the rocks that are most prominent that are least wet. Sediment is the riverbed on which the river flows."

"What is a right when it comes to a river?"

"It is a tension we agree to hold between ripples."

"And is the river a morality?"

"The greatest of those rocks that appear on the surface of society are delivered by time and the actions of the ripples that came before them. Morality is not the choice of individual ripples, but rather of its society. We share in the morality of our joint flow. Yet it is not the river."

"How should we flow?"

"With recognition of the river in the tensions we set into the course."

For a while, the smaller of the two ripples considered this, as it travelled downstream in company. Around the rocks it flowed, and over the riverbed. Eventually it asked:

"What is a morality of flow?"

"It is not in our tensions nor how we experience the flow, but the nature of our ripple that is remembered. And not the conscious remembrance, but the imprint we make on the river’s course."

On reading this, my son related a passage from `How Do You Live?', in which Copper's uncle writes to Copper. I quote the relevant passage from the book here:

First, you might notice that the great people and heroes that loomed so large in your eyes until now were, ultimately, no more than drops of water drifting in that great stream.

Next, you'd surely see that no matter what things those extraordinary people did, they were exceptionally fleeting, unless their work was firmly bound to the current of the stream.

Some among them, watching this stream, pour the whole of their brief lives into it, devoting their extraordinary abilities to driving it forward properly.

Still others, in an effort to further their own individual goals, are completely unaware that they are helping the stream to advance.

And then there are those in the stream who, however much they may surprise the world with their brilliance, are not of the slightest use to the great current. No, there are more than a few who may be called great or heroic, but instead of advancing the flow, they work instead to try to reverse it.

And finally, there are times when one hero will do many things, some with the current and others against. In the course of history, many people arise and do many different things, but ultimately, if what they do is not consistent with the flow of that current, all the accomplishments of any one person will, finally and fleetingly, fall to ruin.

Back to top

Letter to My Son on Turning Ten

30th June 2024

On Turning Ten

One of the most affecting poems I've read in my life is `On Turning Ten' by Billy Collins. This is the poem:

The whole idea of it makes me feel

like I'm coming down with something,

something worse than any stomach ache

or the headaches I get from reading in bad light--

a kind of measles of the spirit,

a mumps of the psyche,

a disfiguring chicken pox of the soul.

You tell me it is too early to be looking back,

but that is because you have forgotten

the perfect simplicity of being one

and the beautiful complexity introduced by two.

But I can lie on my bed and remember every digit.

At four I was an Arabian wizard.

I could make myself invisible

by drinking a glass of milk a certain way.

At seven I was a soldier, at nine a prince.

But now I am mostly at the window

watching the late afternoon light.

Back then it never fell so solemnly

against the side of my tree house,

and my bicycle never leaned against the garage

as it does today,

all the dark blue speed drained out of it.

This is the beginning of sadness, I say to myself,

as I walk through the universe in my sneakers.

It is time to say good-bye to my imaginary friends,

time to turn the first big number.

It seems only yesterday I used to believe

there was nothing under my skin but light.

If you cut me I could shine.

But now when I fall upon the sidewalks of life,

I skin my knees. I bleed.

Billy Collins is an American poet, and was Poet Laureate of the United States between 2001 and 2003. He seems to have published `On Turning Ten' in the Paris Review in 1993 (see www.theparisreview.org/poetry/1874/on-turning-ten-billy-collins), implying he wrote it roughly when your mother and I were turning 10. Perhaps he had heard about, and was writing a poem for, us? Or perhaps he is talking about something relatively universal to the human experience. The poem seems to have resonated with many, at least in American society. It affected me as I thought about you coming up to your own tenth birthday.

As you can read, `On Turning Ten' tells of the melancholic process of `turning the first big number', since it brings the complexity of emotional maturity - `This is the beginning of sadness' - and the disappointments of that maturity as your inner light turns into base blood. A bicycle becomes merely a physical object, leaning according to the laws of gravity rather than of your imagination. And the possibility of becoming a wizard slips from your grasp. The poem brilliantly exposes how some process common to many societies drains life from the imagined self, and from the possibilities of the human experience. It implies that the practicalities of adult life take magic away from the world.

Your light continues, and can continue, to shine

You are currently sitting beside me, repeatedly reading aloud quotes from the `Wings of Fire Legends' novel ``Dragonslayer'' and then laughing and flashing your brilliant smile at me. Despite having hit that threshold Billy Collins talks about, you continue to be able to commune with that light deep inside you. You are remarkable in how close you have let that light shine through in your first ten years. The intensity of mission you had when you used your pocket-money to buy a drink token for the homeless in Bristol will stay with me forever.

This letter commends you for that, and encourages you to keep that light at the core of who you are. Childlike some may think it is; I'd say it is rather a universal feature of a good life that so many allow the complications of ageing to obscure. Joshua - you have a good chance to hold on to that light. To continue to have that light shine through your bleeding. Rather than let maturity press your light deep into obscurity, build a prism with your age. Let your light shine as brightly each year as your ages allow. In that prism you can see life's many colours.

Where Mr. Collins is certainly right is that the rainbow of responses one naturally develops as one matures becomes richer and more multi-faceted over time if you allow it. Yet for me, what ageing means has been mediated by the philosophical lens (or prism) through which it is lived, and through which it is viewed. You have the chance to live a life that embraces Mr. Collins' warning and makes your rainbow all the richer for the mid-afternoon light through which it passes.

Thus the nature of the prism you build - the way you understand how the light filters through you - will determine its impacts. That prism is your philosophy - your system of beliefs about the world. Keeping your light shining at the heart of who you are will require you to embrace your philosophy consciously. Without that embrace, I worry that many of the societies in which you are embedded default to a rather binary version of the world. Such a binary view drains the colour from much of experience. So Mr. Collins will turn out to be correct if you simply take on the world view he is summarizing.

My own process of building a prism

When I was a few years older than you, I began to find myself struggling with the lens I had inherited - from my family, from my community, from my society. In many ways it made ageing into a battle, with a perspective that was tied to my limited experience of the world. Even the religious upbringing I had had - ad hoc yet diverse - drove a limited view of existence that made me uncomfortable.

The greatest moment of my life was the point when I developed a desire to overcome these adopted beliefs and forge a path I grew myself. Whenever that moment was, it was the foundation for my wanting to respond to the process of maturing on terms I could defend in some way.

In time, I found myself falling for a philosophy that I have come to call `social philosophy': one in which the fundamental lens is the social interaction, rather than the individual experience. It took me many years to develop what I believe is a defensible way to view the world. Yet by the time I met your mother at 20, I had the pillars in place. And these evolved, slowly at times, to see the world in a different light to that described by Mr. Collins. For your mother, she came to see bicycles - leaning against the garage or whizzing along the road - as key pieces of the puzzle for better cities, and better futures for us all. I came to see wizardry in the ripples one can make by investing in public goods.

What prism will you build?

What I want you to take from the first part of this letter is that it is what pillars you lay down in the decade to come that are most likely to determine the nature of the life you will lead. For some it occurs later, but for many it is in the decade you have just begun that the pillars of your philosophy will be set.

So set them well. As they will be what makes you who you are. They will determine whether you bleed for something. Or if your bleeding is part of an un-examined process of falling from one year to the next buffeted by the forces that Mr. Collins presents in `On Turning Ten'.

Whatever your decade ahead, let it be the foundation for your examined self. Let it be the foundation for magic in your life. Let it be the platform for your light to keep shining through.

On Turning Ten Again

If you follow my path, and the path of many of those I find resonance with, the next decade of your life will set out the philosophy with which you judge the passage of time itself. When you turn `ten again', you will most likely be you. And so rather than lose the opportunity of a lifetime, let me tell you about my philosophy. While the first section of this letter asked you to examine your world and choose foundations and pillars through which to explore it, this section tries to win you over to my way of seeing things.

I will do so in a way that I hope will be useful even if I don't convince you that my way of seeing things is one you should adopt: by asking some of the fundamental questions of life. I suggest you try to grapple with these at some point.

Who are you?

When you smile that beautiful smile at me, is it `yours'? Or is it something that can only be understood by understanding your society (some conception of the world that lives beyond your conception of yourself)? Can we even conceptualize your smile independently of the society in which it is flashed? Is your smile in some way down to those who influenced you to smile in the way you do? And what would your society say is the very definition of a `brilliant smile' (which you surely do have)? Could your smile change? And if so, is it the individual smile or how it is influenced from elsewhere? But if it can be influenced, doesn't that mean that your smile is not only yours, but rather also the product of your society? If your answer to any of these questions concedes that it is `society' that is part of your brilliant smile, then society constrains, shapes and determines you. You are - in part or in whole - a product of your society.

I could take any aspect of your life, from your smile to your most fundamental beliefs - such as those about God - and make the same argument. If what makes you up can be said to be determined, even partly, by society, then you are a social entity; something defined by the social interactions around it.

If at first you do not believe that, think for a moment about what a philosophy of independent - non-social - entities requires. How would you say you were formed? How would you say you take action? How can those actions have consequences? If someone was to argue that your smile existed in a vacuum, irrespective of the society in which it occurred, ask about the nature of that world - independent of us but relevant to us. Famously Aristotle argued for a pure state of `forms' independent of any interaction. Yet any bridge from the world of forms to one where we have influence over the relationship to such forms brings us once again back to social philosophy. For me, it is in the mapping to any part of society - including you - that non-social philosophies fail.

I believe that this simple conception of ourselves as social entities has a huge range of consequences for one's philosophy. What I call `social philosophy' has formed the foundation of what I believe. My explorations have been around what the corollaries (consequences) are when one takes social interaction as the foundational assumption of philosophical thought. As I have fleshed out these `corollaries', I have found they string together a system of thought that is far more defensible than any other I have come across.

What is `truth'?

The first consequence of thinking of you as a `social' entity relates to our conception of truth. In social philosophy, there is only conceptions of societies, and thus by definition it is within these conceptions that truth is formed. There is nothing else in which truth can be conceived. That means that truth arises from society, and there is not a conception of a truth outside of that - including at the individual-level. Irrespective of our perceptions of truth, it is in our interactions within society that a truth is formed.

This discussion leads us to the idea that truth is social. Not yours. Not mine. Ours. In social philosophy, that is true of all features of the world, including truth. And so who you are - and how closely you align yourself to truth - is a purely social activity.

Yet the society that you and I make up on the couch, and the one that also includes your mother are different. And as such so is the conception of truth. Each society - by definition distinct - has its own conception of truth. That is not to say there are not universal elements of truth in the overlap between different societies. But they are distinct. As such, in social philosophy there are multiple conceptions of truth. This means multiple conceptions of truth for you to explore and appreciate; appreciate the commonalities (perhaps universal truths) and differences.

Your society will therefore be the launch point of your understanding of who you are, and if you are driven to it, towards undertaking truthful action. It is in fact this very process - of society restraining your form and charting out a `right way' ahead - that underlines `On Turning Ten'. It is in my view a poem about socialization, or social philosophy. That society defines the process Mr. Collins lays out, is down to the structure of the society he discusses. And I think he characterizes the society of the United States very well. But it is still just a consequence of the society that the United States has chosen to form. By seeing the world through social philosophy, you can become aware of that fact, and must assess whether you believe in the constraints that have defined you (or the you that Mr. Collins implies). Are you happy with those? If not, can you rebuild your society towards a more defensible self?

What is your relationship to `others'?

As you can probably tell from the above, social philosophy thus puts your relations with others as central to philosophy. Others can be the broad society of the world, from Nature to your family. Your interactions with `others' will determine who you are and who others are.

Let's take those two pieces separately. First, your interactions with others will determine who you are. So as you walk around, smile, read books about dragons, and so on, you are bringing your society along with you. That is what has defined you, and as such self-reflection is about understanding the society that you represent. In social philosophy, it must be that you are a society for otherwise you would not exist. You must learn to get on and productively engage with the society that makes you up.

The second is that because you are influencing and determining others, your boundary is not physical. It is social. You are already spread across numerous others. And as you echo out through society, you must decide the nature of the self that you project. That will determine who you are in others. That is an exciting aspect about growing up that Mr. Collin's poem does not touch on - that as you grow into your wider social self, the opportunities for wizardry are far greater. As your light can spread throughout society, it grows all the stronger inside you.

`Technical Aside': How can I reconcile my beliefs with other `schools of philosophy'?

Much of my teenagehood I took an interest in the writings and philosophies of famous religious and philosophical writers. I thus mention here some reflections on that exploration, since I would suggest it is part of your next decade. Some would say there is no finer way to explore philosophy than by reading the great philosophers. I would disagree. I think that philosophy is by definition a lived endeavour. In a social philosophy, moving towards different conceptions of God requires us to understand the philosophy of others. And that is best achieved by engaging with and learning from other people. Yet reading the words of those made famous for their philosophical writings is a powerful complement to all this, as it is a platform for interpreting the data you gather from society. I would not limit myself to the classical philosophers however, as I believe Ghandi had important things to say as well as Nietzsche. Importantly, `deep thought' should be applied equally to any aspect of your philosophical investigation: lived, read, or otherwise.

When you read philosophy, you may find that schools of thought are contradictory, or even pitched against one another. In contrast, social philosophy is a framework to reconcile the tensions that arise from many schools of thought. That is partly because many schools of thought could be said to be social philosophies. And at least as far as I understand it, little work has been done on investigating `social philosophy' as an abstraction in itself. The closest vein of work that I have found is `communitarianism'. But it is a niche topic. If I were to do another PhD, I would want to do it in philosophy and extend the implications of communitarianism to a much broader set of primitives than has been done so far. But that is the topic for another letter.

Let me show you what I mean. Let's take a central tension in modern philosophy: the role of nationalism and internationalism. Are you a nationalist, and believe that the nation-state is the prime lens of society; or are you an internationalist, and belive that humanity writ large should be the prime lens of society? If both, what is your framework for bringing these perspectives together? This is of particular importance to a boy like you, who has origins and affiliations that cross national borders.

In social philosophy, the society that makes up the nation is distinct, and thus has its own truth. That truth brings its own value to the world. The same can be said of any society/nation. `Ranking them' is hard, since each truth is unique. At the same time, the truth these separate societies brings to the world is enhanced when it is relative to another society, of which a `nation' is a natural formation. The British `truth' is in fact richer in its interaction with the German `truth' because now not only is there a truth in each nation, there is the value they bring by expanding the `super set' of society to the other. The notion of God has expanded, and the overlap in their truths has created a `universal' sense of God. And so each piece of the national-international interaction has value: the two `truths' of the nation states, the overlap in their truths, and the truths that exist outside of that overlap. Each is a distinct conception of God. My answer therefore to this debate is to see the value in each element, and explore the corresponding conceptions of God within it.

So read, my boy, read. Listen to what other authors have said. But also listen to those who have not written their philosophy in abstract words. Appreciate the myriad truths and corresponding conceptions of God that your societies offer. Live and through that living see philosophy written out in the way the world interacts; with you, with those you are fortunate enough to observe yourself, and in the numbers and stories that you hear from elsewhere. Use it all to determine your prism, and to fuel that prism with light. And if you have been swayed by my suggestions that society is a useful lens to understand the world, bring it all together in your heart as a reflection of the society you yourself represent.

On Turning Ten Again and Again

The final section of my letter to you at ten tries to focus on you a little more. Much of what I've written in the first two sections could have been written to any child turning their `first big number'. So let me reflect a little on all that you are, have become, and I expect will be, in light of what I have laid out above.

You have a unique truth

A simple corollary of taking a social philosophy perspective is that your truth is unique, since your society/social constraints are unique to you. By definition, if there was something else that had the same society/social constraints as you, they would be indistinguishable to you. And therefore, whatever truth I have is distinct from yours. I have chosen to write up, and advocate, my philosophy for you since I believe our society's have a lot of overlap. And as such, our truths likely overlap a lot. But they are distinct in ways I cannot understand.

This tension is threaded through this letter, and throughout our lives together. It is expressed beautifully elsewhere. Though I have structured the discussion here partly around `On Turning Ten', another literary quote has affected me deeply as it relates to your upbringing. In Marcel Proust's `In Search Of Lost Time', the young Marcel confronts a painter named Elstir with report of his past transgressions. Elistir is not apologetic, but rather responds,

``There is no man," he began, ``however wise, who has not at some period of his youth said things, or lived in a way the consciousness of which is so unpleasant to him in later life that he would gladly, if he could, expunge it from his memory. And yet he ought not entirely to regret it, because he cannot be certain that he has indeed become a wise man—so far as it is possible for any of us to be wise—unless he has passed through all the fatuous or unwholesome incarnations by which that ultimate stage must be preceded. I know that there are young fellows, the sons and grandsons of famous men, whose masters have instilled into them nobility of mind and moral refinement in their schooldays. They have, perhaps, when they look back upon their past lives, nothing to retract; they can, if they choose, publish a signed account of everything they have ever said or done; but they are poor creatures, feeble descendants of doctrinaires, and their wisdom is negative and sterile. We are not provided with wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one else can take for us, an effort which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world"

As a father, I take the central message of this passage to be `pity the wise man's son'. Or at least, pity the son of a man who is rather convincing. The father's truth will always be distinct to the son's. And as such, you must not be too swayed by my arguments, or overarching beliefs. My philosophical framework implies you must find your own truth.

Thus, having poured effort into making the second section of this letter convince you of my philosophy, I remind you of the fact that even if I could determine the right philosophy for me, it would not be the right one for you. Whether it would differ in detail or in spades, you are likely best placed to work that out.

I am someone who is passionate about my beliefs, and have shared them with you almost without hesitation. Yet, I will never be able to talk directly to your truth. I hope that my thinking is useful for your journey. But it can be no more. It is no substitute for your own explorations.

Your uniqueness is loneliness and commonality

That uniqueness of your truth means a lot for your experience of the world. Clearly, since no one else truly has your truth, you are likely to feel alone. This is something we have already observed in how you interact with your society. You are rarely ready to fold into the general, and prefer to navigate the margins. That is how I have often felt as well. Yet the loneliness of marginality is a direct consequence of constructing a social philosophy. Everyone is an island. If they were not, having the same society, social constraints, and truth, they would be you. And thus, in my philosophy loneliness is simply a fact of life.

This universality of loneliness is our commonality. Everyone experiences it. Perhaps differently; but it is there for everyone, whether they appreciate it or not. And so our journey is to navigate that loneliness together.

So for someone like you - that struggles with your common experience of loneliness and your frequent passion for connection - you are perfectly equipped to explore this balance. In fact, once you realise that this is the lot of everyone - that you are no different - and yet you have already got some of the skills to appreciate God in all their forms, I am hopeful you will be all the more excited about taking that path.

We are all connected by overlapping social constraints

Since we will only be able to engage with entities that share some social constraints with us, it must be that the truths of everything we can share society with overlap in some way. I distinguish the concept of the joint/overlapping parts of truths of different societies as Truth with a capital `T'. You will see that throughout my writings if you ever go back to read them. And this is the purest form of God. Not that it is the most comprehensive. In fact, by definition it is not comprehensive, as it is only made up of the superset of overlapping parts between different truths. But it is what has typically been conceived of as `God', since it is universal. By definition, my `Truth' is universal, since it is made up of the truths of all those in the larger society.

How does this relate to you? At the same time as being someone who is often comfortable in novelty, you are someone who has always had a deep capacity for connection. With ideas, with people, and with experience. You do not really do things by halves. So that capacity is a bridge to the higher and more pure forms of truth. You should lean into that. You should believe in some form of God. While it is your choice what God's nature is, I pray you believe in something higher than yourself you can call God.

To get to that higher Truth that I write about above, you must find a bridge to others. If you stick to appreciating only your truth, then your truth will always be the lower case `t' type. To move towards the upper case `T' type, you must find bridges to other truths. You must empathise, appreciate, and learn. Yet you will - by definition again - never get there; it is only in the process of searching that you find a solution to your loneliness. God will be created in the interaction between your and others truths. You can access that truth only by experiencing the interactions between you and wider society. And the more you take that path, the greater your appreciation of, and links to, the upper case t `Truth'. You can never become one with the purest form of God; you will always be part of the super-set notion of God.

Why does this matter to me? Basically most of my life has been about exploring the characteristics of God. And it has driven me like nothing else. It has given my life more meaning than anything else. Love is a feature of God for me; as is public service. But it is an amazing `organising framework' for our explorations of that overlap in truths. Those who don't have it seem so lost by the complexity of so many different truths and by their overlap, that they seem absent from their lives in multiple ways. I simply do not wish that future for you.

Final Words

I love you. Though I hope my everyday, speciality, and once-in-a-lifetime actions show you that. Why would someone spend so much of their time writing out a letter of advice like this than because they care for you so deeply that the edge of that love is lost over the horizon?

Your prism provides you with a window through which to interpret and perhaps appreciate the ``late afternoon light" of life. My love for you drives me to want to equip you with ways to manage the complexities of the world. I hope there is some of that in this letter.

But at the same time, it provides you with a way to consider which actions to take in the world. Whether you take on some features of my own beliefs or forge your own, let your actions be guided by self-examination and a conscious process of philosophical enquiry.

You are someone who has already show the depth of their intellectual and emotional talents. Use them to build a prism through which you can see and appreciate the rainbow of the world, and for others to be able to see the rainbow inside you.

Happy birthday my son. May the words in this letter be a useful guide for your decade to come. Ojamashimashita.

Annex: ChatGPT's effort

I have taken to using AI to act as a benchmark for writing efforts I am undertaking at this stage of life. As such, I asked ChatGPT to write a letter to you; it's response to the following prompt is below: ``please write a letter to my son on the occasion of his 10th birthday regarding how to live life in a spiritually and philosophically righteous manner, including quotes from relevant philosophers"

Dear [Son's Name],

Happy 10th Birthday!

As you reach this milestone, I want to share with you some thoughts on how to live a life that is both spiritually and philosophically righteous. Life is a beautiful journey filled with endless opportunities for growth, learning, and connection. Here are some principles to guide you along the way, inspired by great thinkers and philosophers who have pondered life's big questions.

Embrace Compassion and Kindness

Compassion and kindness are the cornerstones of a righteous life. The Buddha once said, ``Hatred does not cease by hatred, but only by love; this is the eternal rule." Always strive to treat others with empathy and understanding, even in difficult situations. Your kind actions and words can create ripples of positivity that extend far beyond your immediate surroundings.

Seek Knowledge and Wisdom

Knowledge is a lifelong pursuit. Socrates, a great philosopher, famously said, ``The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing." Stay curious, ask questions, and never stop learning. Whether it's through books, experiences, or conversations, every moment holds a lesson. Wisdom isn't just about acquiring information; it's about understanding how to apply that knowledge to make better decisions and enrich your life.

Practice Integrity and Honesty

Living with integrity means being true to yourself and others. Confucius taught, ``The superior man understands what is right; the inferior man understands what will sell." Always strive to do what is right, even when it's difficult. Honesty builds trust and respect, both essential components of meaningful relationships.

Cultivate Inner Peace

Inner peace comes from within, and it's essential for a balanced life. Lao Tzu, the ancient Chinese philosopher, said, ``He who conquers others is strong; he who conquers himself is mighty." Spend time in reflection, meditation, or prayer to connect with your inner self. This practice will help you stay grounded and resilient in the face of life's challenges.

Embrace Simplicity

In a world filled with distractions and material pursuits, simplicity can bring clarity and joy. Henry David Thoreau, an American philosopher, wrote, ``Simplify, simplify." Focus on what truly matters—your relationships, your passions, and your well-being. By simplifying your life, you'll find greater contentment and purpose.

Act with Purpose and Determination

Live with intention and purpose. Aristotle believed that ``happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim and end of human existence." Find what makes you happy and pursue it with determination. Set goals and work towards them with perseverance and dedication. Your efforts will lead to a fulfilling and meaningful life.

Foster Gratitude

Gratitude is the key to a joyful life. Marcus Aurelius, a Roman emperor and philosopher, advised, ``When you arise in the morning, think of what a precious privilege it is to be alive—to breathe, to think, to enjoy, to love." Take time each day to reflect on the blessings in your life. This simple practice can transform your outlook and increase your happiness.

Build Strong Relationships

Cherish and nurture your relationships. Epictetus, a Stoic philosopher, said, ``We are not disturbed by things, but by the views we take of them." Surround yourself with people who uplift and support you. Strong relationships provide a foundation of love and security that can help you navigate life's ups and downs.

As you step into this new chapter of your life, remember that you have the power to shape your journey. These principles are just a guide; ultimately, your experiences and choices will define your path. I am incredibly proud of the person you are becoming and excited to see the amazing things you will achieve.

Happy Birthday, my dear son. May your life be filled with wisdom, love, and endless possibilities.

With all my love,

[Your Name]

Back to top

1 | 2 | 3

|